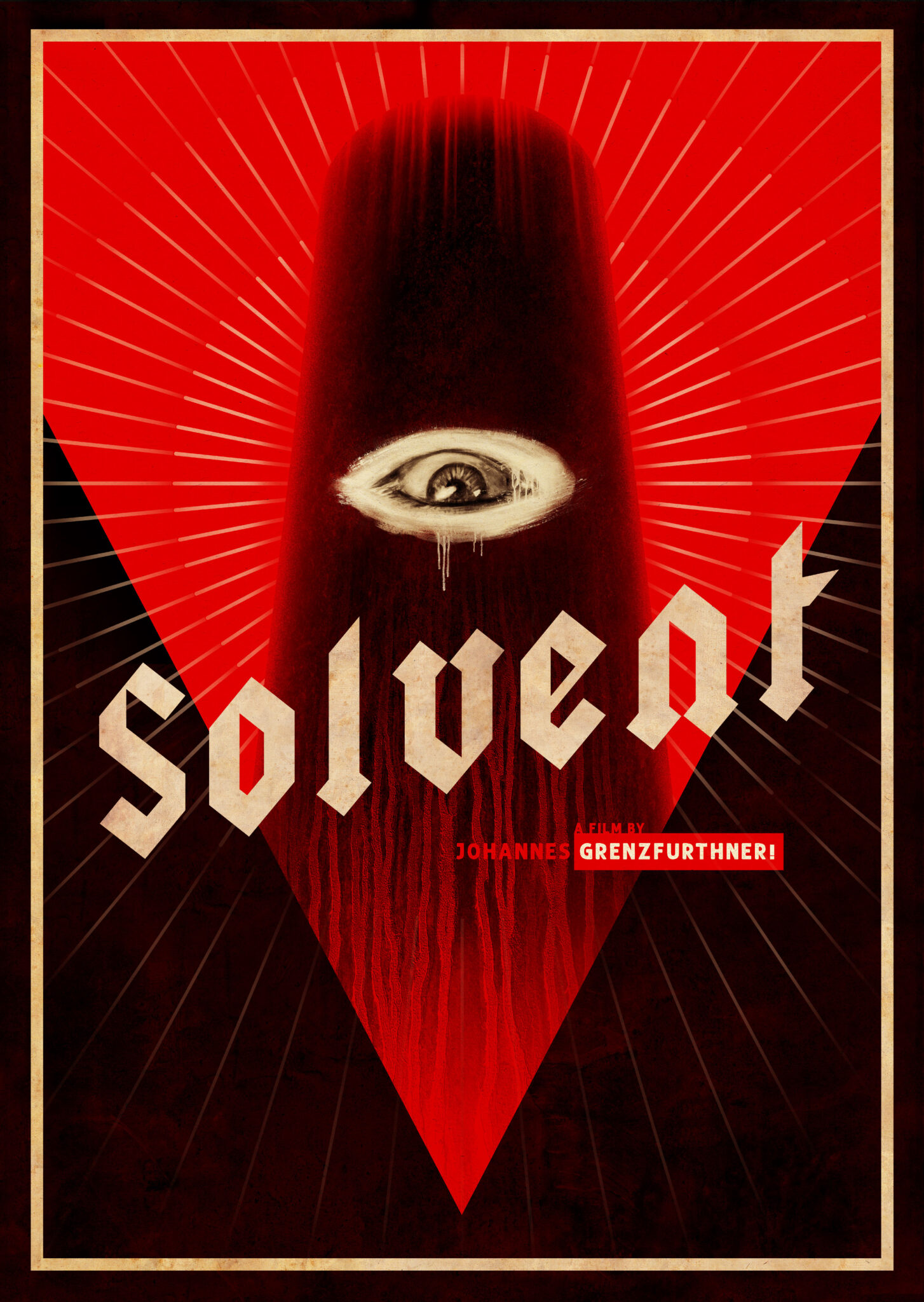

“We Are All Holocaust Deniers“: An Examination of “Solvent“ by Johannes Grenzfurthner

In Johannes Grenzfurthner’s genre-transcending Solvent, historical reality and psychological horror intertwine, creating intricate and disturbing layers of memory, guilt, and destruction.

Three days before Austria’s national elections in September 2024—an election that saw the far-right FPÖ surge to first place—I found myself sitting in a packed theater in Vienna for the premiere of Solvent at the Slash Filmfestival. As the lights dimmed, the air was thick with anticipation, not least because Jon Gries, one of the film’s leads, was in attendance, intensifying the already charged atmosphere of the film. But what struck me most was how this film—this unsettling exploration of buried traumas—was premiering at such a politically charged moment. In Solvent, Johannes Grenzfurthner doesn’t simply create a horror film; he uses the genre to expose the festering wounds of history. As I witnessed a graphic descent into madness, it felt disturbingly close to the surface—much like Austria’s own grappling with its past and present. What unfolded on screen wasn’t just a historical reckoning, but an emotional confrontation with the unresolved legacies of Austria’s past and its uncomfortable echoes today.

On the surface, the narrative appears straightforward: Gunner Holbrook, an American contractor, and Dr. Krystyna Szczepanska, a Polish historian, are searching for physical evidence of Nazi war crimes on the farm of the dead Nazi officer Wolfgang Zinggl. They discover something, but it’s not the historical documents they are looking for, and the macabre becomes a language to articulate the unspeakable horrors they face.

Probing deeply into unresolved traumas

Artist and filmmaker Grenzfurthner (Masking Threshold, Razzennest) is known for breaking conventions, and this film is no exception. Never one to shy away from uncomfortable truths, he uses the horror genre to probe deeply into unresolved traumas. This isn’t a film concerned with jump scares or other typical tropes, although the director loves to play with those expectations.

At the heart of Solvent is an exploration of the disturbing and the bizarre. The grotesque in this film serves as more than just shock value; it’s a narrative device that helps to articulate the complexities of culpability, memory, and trauma. Holbrook’s form, warped by his proximity to the cursed subterranean realm, becomes a symbol of how the burdens of history physically manifest in the human body. Florian Hofer’s masterful POV cinematography intensifies this transformation. The imagery carries a deep philosophical weight, reminiscent of German literary traditions that use the grotesque to reveal the absurd and cruel aspects of human existence. Though the grotesque elements certainly do shock—I’ll never look at my penis the same way—they also serve as a powerful way to reveal how unresolved trauma and moral decay can fester and manifest in uncanny ways. His arc of redemption, as any cultist fan of “Save the Cat!®” might assure you, is quite unconventional and… liquid.

Dark themes and humor

Despite its dark themes, Solvent is remarkable for its humor. Grenzfurthner expertly balances the weight of his themes with moments of dark, biting humor, springing forth from the absurdity of Holbrook’s obsessive pursuit to the bizarre discoveries in Zinggl’s farmhouse. This humor doesn’t soften the blow but amplifies the discomfort, leading the audience to laugh at absurdity only to feel the weight of that laughter afterward. It’s this humor that gives Solvent a unique edge—while it’s a film about national trauma and moral decay, it also reminds us that sometimes, the only way to confront horror is through laughter.

Grenzfurthner’s use of old family photographs—including childhood images of himself and his grandfather Otto Zucker—to portray Zinggl and his grandson Ernst Bartholdi transforms the farmhouse into a metaphorical palimpsest: a layered text with traces of the past remaining visible beneath the surface, despite attempts to erase or overwrite them. The farmhouse in Solvent – strewn with strange objects, from bottles of urine to dark, crumbling cellars—embodies this concept, as history’s detritus remains ever-present, even when we try to bury it.

One of Solvent‘s key themes is the disturbing erotic charge underlying the destructive ideologies of National Socialism. Zinggl’s fixation on urine, for example, reflects the way fascism eroticizes power and annihilation through symbols of degradation. And this ties into a broader exploration of the occult and contemporary pseudoscientific movements like New Age practices and alternative medicine, exemplified by Ryke Geerd Hamer’s “Neue Germanische Medizin,” which tied pseudoscience to ultra-right ideologies. Zinggl’s involvement with this fringe belief system draws a direct line between the irrationality of Nazi-era ideologies and the contemporary resurgence of far-right movements. In this way, the film exposes how dangerous beliefs continue to circulate, infecting generations. The cursed water system could be seen as a metaphor for these dangerous beliefs—an invisible, insidious force that warps reality and infects those who come into contact with it.

Disturbing exploration of antisemitism

Perhaps most disturbing is Solvent‘s exploration of evolving forms of anti-Semitism. Here, Grenzfurthner and his talented co-writer Ben Roberts go beyond historical critique and connects Nazi anti-Semitism to its modern manifestations, particularly through Zinggl’s stupendous anti-Zionist rhetoric, using quotes from conversations that Grenzfurthner heard at soccer matches and on anti-vaxxer/anti-COVID demonstrations. Grounding the film in reality, cameos by ultra-right figures like Gottfried Küssel and Martin Sellner make it all even more chilling, adding a layer of unsettling realism.

As Grenzfurthner told me at the premiere, “We are all Holocaust deniers. Our minds diminish its reality, unable to grasp the full extent of what occurred.” This statement encapsulates the central tension of Solvent – the impossibility of fully comprehending the horrors of the past, and yet the moral imperative to try. (Careful, spoiler!) Holbrook’s final act, transmitting crucial historical information to Szczepanska before his body disintegrates, symbolizes the struggle to preserve and confront historical truth, even as time erodes our ability to grasp it fully. Pieter de Graaf’s haunting score creates an aural atmosphere that leaps between beauty and horror, like a demon, amplifying the film’s gripping depths.

Gunner S. Holbrook is the emotional core of Solvent. Jon Gries’s impressive performance keeps Holbrook as the compelling center of the film. Despite his horrifying past, Holbrook embodies a desperate need to reconcile with history, even when doing so means becoming part of its darkest chapters. His brittle, truthful, and disturbing conversations with Dr. Szczepanska (portrayed by the mesmerizing Aleksandra Cwen) are simply captivating, and you surely won’t forget the performances of the rest of the ensemble: special shout-out to Roland Gratzer’s strangely loveable Weinhappl, and Grenzfurthner himself, who outdoes himself as “that fucker Bartholdi.”

So, I assume the dear reader has already understood: I love Solvent. It is one of the most remarkable films of 2024. Grenzfurthner’s uncompromising artistic vision lingers (or rather: seeps) long after the credits roll, leaving a gespenstische (haunting) impression that is intellectual, emotional, and bat-shit crazy. Not sure all viewers will be able to enjoy it, but enjoyment is overrated. For those willing to engage with its complexities, Solvent offers a reminder of history’s terrifying persistence.

The US premiere took place at Nightmares Film Festival in Columbus, Ohio. Upcoming screenings are scheduled in Italy, South Africa, the UK, and other locations.

Peter Blok grew up in Maastricht, the Netherlands, and studied graphic design. How he ended up in Denver, Colorado, working for a defense contractor is a long story. Let’s just say it all ended well, and now he lives happily in Vienna, Austria, with a cat and a parrot, working for the United Nations as a cinephile.

Bildquellen

- solvent (20): Filmstill "Solvent"

- solvent (15): Filmstill "Solvent"

- solvent (1): Filmstill "Solvent"

- Solvent_poster_large: Filmplakat "Solvent"